Logos are important. They are a team’s identity, the common element that we recognize, that we react to. If a Yankees fan sees those two red socks on the back of a car, they know the car belongs to a Red Sox fan. If you want to know the power of a logo, break out your Cowboys t-shirt at FedEx Field (please do not do this).

I have limited background in design. I’m no expert. I just like logos. I’m not going to break down each element of a logo, but I do look at the font, the colors, the link with the team name, the complexity (or “busyness” you could say) and so on. Some logos just have that somethin’ special.

I’m limiting the pool to the Big 4: MLB, NFL, NBA and NHL. Defunct or relocated teams count. MLS isn’t old enough, and there are way too many colleges out there. A current logo qualifies as historic if it was being used, say, since 1985 (over 25 years).

10. Chicago Cubs: 1979 – present (MLB)

10. Chicago Cubs: 1979 – present (MLB)

The Cubs have been around forever. If it weren’t for that pesky Great Chicago Fire costing them the 1872 and 1873 seasons, they would be the oldest sports franchise in the country. Since the late 1900s, the Cubs have kept the same basic theme with their logo: A large “C” and something in the middle. In the first part of the century, it was usually a bear. Since the 30s, it’s been “U-B-S.” The latest (and best) incarnation came about in 1979 and has seen the likes of Sandberg, Dawson, Maddux and Sosa. It’s simple and clean and contained completely within a circle. I don’t typically like logos that are entirely contained within a circle, but the interior “C” helps to break up the circle’s impact visually. You can never go wrong with red and blue. It doesn’t tell you anything about Chicago or their mascot, but it does tell you something very important about the Chicago Cubs: They’re a historic franchise that have never needed a huge makeover. Their logo is a fairly modern take on a simple concept. It’s proof that sometimes simpler is better.

9. Portland Trail Blazers: 1970/71 – 1989/90 (NBA)

9. Portland Trail Blazers: 1970/71 – 1989/90 (NBA)

This is the lone NBA representative on this list. And it seems an unlikely choice. There’s nothing in this logo that tells you anything about the team. Absolutely nothing. Some people suggest that the logo is a backwards “p” and “b” but I can’t verify that. The font used in the wordmark is certainly echoed in the logo. And if you’re willing to take it a step further, you could probably get a “t” out of there. Anyhow, at first glance, it does have some things going for it: Clean lines, a simple and distinct shape and it’s self-contained without being completely enclosed in a circle. The logo creates a sense of movement, and it feels dynamic despite its simplicity.

I also like the choice of non-traditional colors. I read one comment that said black and red were used to mark the Oregon Trail but haven’t been able to verify that via an admittedly brief Google session. If it is true, that’s a stroke of genius. But there’s another stroke of genius, one that’s far more subtle. Both the red element and the black element are made up of five lines. And, of course, basketball is a game of five on five. So you have a (very) abstract representation of the game the Trail Blazers are playing. You can even take it further and suggest that sense of movement brings the five lines to meet in the circle at center court. One last thing: It just screams classic 70s.

8. Minnesota North Stars: 1967/68 – 1973/74 (NHL)

8. Minnesota North Stars: 1967/68 – 1973/74 (NHL)

Perhaps hockey teams seem to spend a little more time than other sports on their image and identity. Or it may be because their logos appear more prominently on their uniforms. It may be because a lot of these teams showed up later on when identities became more important with more exposure. Until 1967, there were only six teams in the NHL. At that point, the league doubled in size. One of those teams was the Minnesota North Stars.

None of the expansion teams of ’67 were Canadian. The team farthest north was Minnesota. And when you think hockey, you look north. Like the Cubs logo, this one is simple and easy to use in various formats. It gives you an idea where Minnesota is in relation to the other American teams and evokes the team’s branding. The “N” has a nice fluidity; it creates a sense of movement that leads you to the star. The star fits snugly into the arrow, which is pointing up, the usual direction for north. Not only does it lead you into the star, but it takes you north to hockey’s homeland. And of course the star is yellow which always goes well with green. When the North Stars moved south to Dallas, they dropped the “North” and the logo lost everything that made it special.

7. Toronto Blue Jays: 1977 – 1996 (MLB)

7. Toronto Blue Jays: 1977 – 1996 (MLB)

This is a complex logo. It has a lot of competing pieces, lots of swooping lines and a non-traditional font. At the same time, for a logo from the 70s, it has a surprisingly modern representation of a blue jay: Angular and abstract. It incorporates Canada’s maple leaf without distracting the viewer from the rest of the logo. While I’m not a fan of using sports equipment in a logo, it seems to work here: The ball creates focus and helps define the logo’s shape that might otherwise seem to sprawl in all directions. The blue is an obvious choice but the red is not. Blue and red verges on the traditional American colors used by a number of teams. But here it provides a contrast that helps to, again, focus the logo and contain its pieces. If you ignore the text, it tells you most of what you’d need to know: the team is Canadian, probably called the Blue Jays and they play baseball.

And when you compare it to their horrible current logo, this logo is a work of art, worthy of a wall at the Louvre.

6. Pittsburgh Steelers: 1963 – present (NFL)

6. Pittsburgh Steelers: 1963 – present (NFL)

You should know this logo. This logo probably violates any rule I could put on paper about what logos should or should not do. It’s completely surrounded in a circle, it contains colors that are not part of the team’s official colors, it’s basically copied from another organization’s logo. And so on. The logo’s history tells part of the story. It was created in 1960 for the American Iron and Steel Institute, and it originally said just “Steel” on the left side. The three shapes on the right side are called astroids, which are “hypocycloids with four cusps” (yeah, I know, just go here). A company called Republic Steel (from Cleveland!) asked the Steelers’ owners about putting the logo, the Steelmark, on their helmets. In 1963, the Steelers asked if they could change “Steel” to “Steelers” and there you have it. The colors do mean something: Yellow is coal, red (originally orange) is iron ore and blue is for scrap metal. So that the Steelers could trademark it, they made the astroids bigger and changed the middle one to red.

So, how does all of this make a good logo? Because what started as the symbol for an industry turned into one of the most iconic brands in not just the NFL but all of professional sports. It shows how seemingly random shapes and colors can come together in a clean, classic design. And to underscore all of that, what amounts to an advertisement for the steel industry turned into the logo for a football franchise that had been around for 30 years before the logo even existed. Can you imagine that happening today? Scratch that and try this: Can you imagine that happening so overtly today?

5. California Golden Seals: 1970/71 – 1973/74 (NHL)

5. California Golden Seals: 1970/71 – 1973/74 (NHL)

Wait, you’ve never heard of the California Golden Seals? Well, you’re in good company. I doubt anyone who wasn’t a hockey fan in the 60s and 70s has. They were part of the expansion in 1967 that also brought the North Stars to the NHL. They were the California Seals, then the Oakland Seals and then finally the California Golden Seals. After that, they moved to Cleveland and then merged with the North Stars. But while they were in the Bay Area, the Seals kept the same basic logo: An abstract seal with a hockey stick coming out of a “C.” I’ll admit that this logo didn’t catch my eye when I first saw it. But like the Trail Blazers logo, it grew on me. There are no hidden pieces, no subtle elements. It’s just a straight logo, and that might be the part I like the most. It’s got a lot going on but it’s not overwhelming.

The “C” is good: As I’ve said, as a general rule, logos should use circular elements to contain most of the logo, not all of it. Even when they were the Oakland Seals, the seal’s head spilled out of the “O” (that was converted from the “C”). The seal is not a simple. Like the Blue Jays’ logo, the representation is remarkably ahead of its time. And like the Blue Jays’ logo, the animal isn’t represented as aggressive, but as neutral or even “happy” as was common before the 90s. The aggressive animal logo phenomenon came later and is all the rage over the past 10 or so years (see the most recent logo changes for the Seahawks, Lions, Dolphins, Blue Jays and nearly every minor league baseball team).

Of course, a seal is a good choice for a team name in the Bay Area, it being home to the California sea lions and harbor seals. Additionally, there was the San Francisco Seals, the minor league team that Joe DiMaggio played for. The fact the seal is holding a hockey stick is something I’d normally dislike but here it helps to balance the composition. There’s a lot of unused space inside the “C” which was filled in with green. I’m okay with that, too, for the same reason: It gives the logo a nice balance and helps the yellow elements stand out.

This is the kind of fun logo you’ll never seen again. It would be considered too flat, too static, too something. But it’s bold and holds up well to this day. It’s a good mix of an old football or baseball logo and something you might see today. To that effect, this is a unique work that we may never see the likes of again.

4. Milwaukee Brewers: 1978 – 1993 (MLB)

4. Milwaukee Brewers: 1978 – 1993 (MLB)

I remember always seeing this logo on baseball cards and thinking, I don’t understand why the Brewers use a glove and ball as their logo. I just didn’t get it. And it took me a while to get it. My wife, on the other hand, got it immediately when she saw it. It’s an “m” and a “b” of course, and it’s flawlessly molded into a baseball glove, the empty space in the “b” serving as a baseball. It has a cartoonish quality to it: The font is bubbly and uneven, the outline is thick and the ball is, well, anatomically incorrect. But these qualities give it that fun quality. It’s a nice reminder that, hey, sports can be fun sometimes.

This logo is also a good example of how a team can create an identity crisis for itself. It establishes an identity, sticks with it for a long time, and then changes it for no apparent reason. This logo was on the hats of Robin Yount, Paul Molitor and Rollie Fingers. And then the team altered its colors, did away with the ball and glove logo and created an entirely new identity. And a decade later, the Brewers brought this logo back as a third uniform. The Blue Jays did the same thing. There’s a reason people like throwback uniforms: They’re usually better.

3. Montreal Expos: 1969 – 1991 (MLB)

3. Montreal Expos: 1969 – 1991 (MLB)

We’re going north of the border again. When I was a kid, I watched the Atlanta Braves on TBS religiously, and they seemed to be playing in Montreal 100 times a year. I always wondered about the logo on their hat: It appeared to spell out “elb,” and I had no idea what that meant. A former co-worker of mine was an Expos fan. (Really, his license plate was “XPOSFAN”.) He told me that it spelled out “eMb” with the “e” and “b” forming part of the “M”. Admittedly, the “M” is hard to see at first, but it’s there and stylized in a way that feels like it represents Montreal well (though I cannot tell you why).

So, why “eMb” then? Well, in French, it stands for équipe de Montréal baseball, which translates into “Montreal Baseball Team.” But, wait, there’s more! Shuffle those letters around and you get “Meb” and they left it in English for you: “Montreal Expos Baseball.”

So in one little, three-color shape you have the team’s insignia, a description of the organization in French and a description of the club. It’s simple and unique and stands out as one of the better baseball logos in history. It may not be iconic like the Yankees’ “NY” or the Brooklyn Dodgers’ “B”, but it’s clever and captures that certain je ne sais quoi.

2. Hartford Whalers: 1979/80 – 1991/92 (NHL)

2. Hartford Whalers: 1979/80 – 1991/92 (NHL)

When the Whalers moved to Raleigh and became the Carolina Hurricanes, this logo disappeared from the sports world. This is one of those logos that probably flew under the radar: It’s a very small city in the fourth sport of the Big 4. I’m not a big fan of whaling and all, but I’m pretty sure there’s no other team called the Whalers in the sports world (unless there’s some small liberal arts college playing Division III basketball I don’t know about). The Whalers’ logo took advantage of an design element you rarely see: Negative space. Think the FedEx logo, the way the white area between the “E” and the “x” forms an arrow. You probably never noticed it. But once you see it, you’ll never stop seeing it. That arrow is the negative space.

In this logo, you have the “W” at the bottom. Pretty obvious. At the top, you have the two flukes. That alone would be a pretty decent logo. But graphic designers are sometimes pretty damn good at what they do. And good ones will use that negative space when it can be used effectively. In-between the “W” and the flukes you have a stylized “H”. So, in one compact space you have the first letter of the city, the first letter of the team name, and a graphical representation of the team name (or what the team name would be killing, I guess). Another nice touch is that the outsides of the “W” are rounded to give it the feel of water. It’s like the tail is coming out of the water.

This logo is similar to the Expos logo in what it accomplishes. It takes a lot of pieces and puts them in a clean, simple form. There’s nothing flash about it. It doesn’t use a lot of colors or any sense of depth to give the team an identity. And like the Expos logo, it manages to endure even though the team itself is no longer around.

1. Vancouver Canucks: 1970/71 – 1979/1980 (NHL)

1. Vancouver Canucks: 1970/71 – 1979/1980 (NHL)

I don’t know where to begin with this logo. So many things are represented in such a simple design. If there’s a problem with it, it’s that people don’t know what’s being represented. It’s too damn good for its own good.

The somewhat obvious: It’s contained within a hockey rink and there’s a hockey stick cutting across the right side. Thus the nickname “stick-in-rink” logo. Some people don’t pick up on the rink but the stick is clear. The colors weren’t just chosen because they look good together (they do) but because they represent three natural characteristics of Vancouver: The blue water, the green trees and the white snow of the mountains. Then we begin to dig deeper. The hockey stick breaks the outline and creates a very, very stylized “C”, and one could go so far as to say that the negative space in the stick itself serves as a very shallow “V”. Then you get to the flat out esoteric: That hockey stick forms the mouth and jaw line of an abstract whale head.

I know a lot of people hear all of this and just shake their heads. That’s the problem I mentioned earlier: A lot’s going on but it’s all really subtle. Even the “C” is subtle. Most people see a hockey stick in a swimming pool. Even if this was simply a hockey stick in a swimming pool, it would still be one of the best logos ever created. It’s clean, simple and nice to look at.

In the end, logos often define a team’s identity. You’ll always know that the hockey stick in the swimming pool logo belongs to the Canucks. The longer a logo sticks around, the more entrenched that identity gets. That’s why some baseball teams can hang on to the most generic of logos (think the Tigers’ script “D”). No sports fan in North America is going to look at that and wonder what team it is. But for teams that haven’t been around since the turn of the century, you have to create an identity and stick with it, good or bad (good’s usually better, though).

I remember being confused. I had played a bit of golf at that point and just began casually paying attention to the PGA Tour. The tour seemed random in a way that nearly turned me off. Every event, from what I could tell, was just a whole lot of waiting around until Sunday afternoon when someone would hit a lucky or unlucky streak, and the tournament would be decided. So, with 18 holes to play, how could there be no chance for Tiger to lose? I wouldn’t really understand for another three years.

I remember being confused. I had played a bit of golf at that point and just began casually paying attention to the PGA Tour. The tour seemed random in a way that nearly turned me off. Every event, from what I could tell, was just a whole lot of waiting around until Sunday afternoon when someone would hit a lucky or unlucky streak, and the tournament would be decided. So, with 18 holes to play, how could there be no chance for Tiger to lose? I wouldn’t really understand for another three years. I’ve thought a lot about why I feel that way, and the honest truth is that the “scandal” never surprised me. Baseball players take steroids. Football players gouge each other’s eyes out at the bottoms of pile-ups. Famous, rich, good-looking athletes cheat on their spouses. I’d love to design a world where that weren’t the case, but I’m only a spectator in this one and never got that chance. I consider myself a pragmatist and wear that term with honor, so it never made sense to me that anyone would be surprised—to say nothing of outraged, shocked and upset—to learn that the wealthiest athlete in the history of the world, in the prime of his career, would be anything less than faithful. This isn’t a value judgment about Tiger’s decisions. It’s much closer to a question of statistics, of how likely it was that he wasn’t doing these things in the first place. Fantastically unlikely. American sports heroes are false idols, and they always will be. That simple realization makes any salacious reveal the expectation, not exception. Sports heroes are not real people. None of our heroes are, and it’s irresponsible to treat them that way—it’s never been why we’ve loved them, and it’s only peer pressure that turns our love into hatred.

I’ve thought a lot about why I feel that way, and the honest truth is that the “scandal” never surprised me. Baseball players take steroids. Football players gouge each other’s eyes out at the bottoms of pile-ups. Famous, rich, good-looking athletes cheat on their spouses. I’d love to design a world where that weren’t the case, but I’m only a spectator in this one and never got that chance. I consider myself a pragmatist and wear that term with honor, so it never made sense to me that anyone would be surprised—to say nothing of outraged, shocked and upset—to learn that the wealthiest athlete in the history of the world, in the prime of his career, would be anything less than faithful. This isn’t a value judgment about Tiger’s decisions. It’s much closer to a question of statistics, of how likely it was that he wasn’t doing these things in the first place. Fantastically unlikely. American sports heroes are false idols, and they always will be. That simple realization makes any salacious reveal the expectation, not exception. Sports heroes are not real people. None of our heroes are, and it’s irresponsible to treat them that way—it’s never been why we’ve loved them, and it’s only peer pressure that turns our love into hatred. The 3-iron into the 18th for eagle on Saturday at the 2009 Presidents Cup, the Saturday 66 at the 2010 U.S. Open and the front nine blitz on Sunday at the 2011 Masters were all-too-powerful reminders of what once was. But with each passing week, with each Did not play that gets logged for Tiger in another major, they look more like mirages and less like sparks capable of reigniting the fire that I loved so much. There’s a sense of cognitive dissonance for me because each instance was, without a doubt, as good as Tiger has ever looked, right up to the 5-wood into the 8th green for eagle on last Masters Sunday. It was perfect. It was also fleeting, and that’s the most disappointing thing I’ve ever learned about sports.

The 3-iron into the 18th for eagle on Saturday at the 2009 Presidents Cup, the Saturday 66 at the 2010 U.S. Open and the front nine blitz on Sunday at the 2011 Masters were all-too-powerful reminders of what once was. But with each passing week, with each Did not play that gets logged for Tiger in another major, they look more like mirages and less like sparks capable of reigniting the fire that I loved so much. There’s a sense of cognitive dissonance for me because each instance was, without a doubt, as good as Tiger has ever looked, right up to the 5-wood into the 8th green for eagle on last Masters Sunday. It was perfect. It was also fleeting, and that’s the most disappointing thing I’ve ever learned about sports.

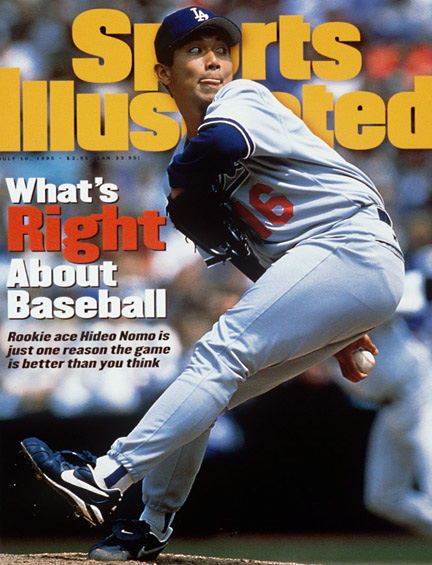

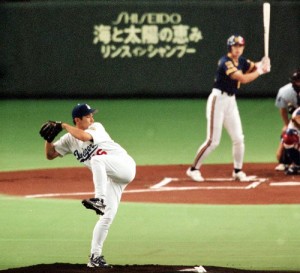

Nomo Mania began in the 1995 season, when he splashed onto the Major League scene with the Los Angeles Dodgers, seemingly out of nowhere, after a bitter contract dispute with the Kintetsu Buffaloes of the Pacific League in Japan. Mesmerizing crowds and bewildering opposing batters at every ballpark with his never-before-seen “tornado” windup style, he finished the season with an impressive résumé, leading the league in strikeouts, a 13-6 record and a 2.54 ERA. And let’s not forget he was the starting pitcher for the National League in the All-Star Game. His performance was even more impressive the following season, going 16-11 and capping the year off with a no-hitter at Denver’s Coors Field, the hitter’s paradise. All these numbers, however, don’t begin to tell the story of Nomo, whose legacy, while paling in comparison to that of Jackie Robinson, warrants a discussion as a future Hall of Fame member for his contributions to the game of baseball as a whole.

Nomo Mania began in the 1995 season, when he splashed onto the Major League scene with the Los Angeles Dodgers, seemingly out of nowhere, after a bitter contract dispute with the Kintetsu Buffaloes of the Pacific League in Japan. Mesmerizing crowds and bewildering opposing batters at every ballpark with his never-before-seen “tornado” windup style, he finished the season with an impressive résumé, leading the league in strikeouts, a 13-6 record and a 2.54 ERA. And let’s not forget he was the starting pitcher for the National League in the All-Star Game. His performance was even more impressive the following season, going 16-11 and capping the year off with a no-hitter at Denver’s Coors Field, the hitter’s paradise. All these numbers, however, don’t begin to tell the story of Nomo, whose legacy, while paling in comparison to that of Jackie Robinson, warrants a discussion as a future Hall of Fame member for his contributions to the game of baseball as a whole. While we can’t give Nomo all the credit for the globalization of baseball in the last decade, the success that he enjoyed encouraged 42 other Japanese players to successfully make their way to the Majors since then. This alone speaks volumes. Sure, Ichiro might have ended up playing in the Majors anyway, but perhaps not as early as 2001. And Nomo’s success certainly influenced general managers across the MLB to look outside of the U.S. to not only Japan, but other Asian countries as well. The infusion of Latin and Asian players into the Majors in the last 15 years, along with the additional revenue the MLB has generated with its globalization initiatives, must, at least in part, be credited to him.

While we can’t give Nomo all the credit for the globalization of baseball in the last decade, the success that he enjoyed encouraged 42 other Japanese players to successfully make their way to the Majors since then. This alone speaks volumes. Sure, Ichiro might have ended up playing in the Majors anyway, but perhaps not as early as 2001. And Nomo’s success certainly influenced general managers across the MLB to look outside of the U.S. to not only Japan, but other Asian countries as well. The infusion of Latin and Asian players into the Majors in the last 15 years, along with the additional revenue the MLB has generated with its globalization initiatives, must, at least in part, be credited to him. Before I continue, it’s important I disclose to you that I hate Michael Vick as much as you can hate someone you’ve never met.

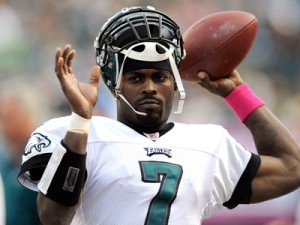

Before I continue, it’s important I disclose to you that I hate Michael Vick as much as you can hate someone you’ve never met. But Vick’s actions aren’t simple. They require analysis way above my pay grade. It’s not as easy as evoking “they’re just dogs.” 99% of those who’ve uttered “they’re just dogs” would not stand by and allow something like dog-baiting to occur in their presence. Vick didn’t simply participate in dogfighting. He led and financed an interstate crime syndicate, and he hosted it on his own property. He hung and drowned dogs who “underperformed.” It’s not an issue of culture—that defense is as racist as it is ridiculous. It’s not an issue of mankind’s dominion over animals. It’s a question about the very value of life. I truly believe that Vick’s lack of respect for life extends to humans. I truly believe that Vick will be forever incapable of understanding the gravity of his actions.

But Vick’s actions aren’t simple. They require analysis way above my pay grade. It’s not as easy as evoking “they’re just dogs.” 99% of those who’ve uttered “they’re just dogs” would not stand by and allow something like dog-baiting to occur in their presence. Vick didn’t simply participate in dogfighting. He led and financed an interstate crime syndicate, and he hosted it on his own property. He hung and drowned dogs who “underperformed.” It’s not an issue of culture—that defense is as racist as it is ridiculous. It’s not an issue of mankind’s dominion over animals. It’s a question about the very value of life. I truly believe that Vick’s lack of respect for life extends to humans. I truly believe that Vick will be forever incapable of understanding the gravity of his actions. Just a few days ago, Nike signed Vick to an endorsement deal four years after they severed ties with him. Forgive and forget? Nike weighed the pros and the cons and they came to the conclusion that it makes business sense to have Vick out there on their behalf. Nike is banking on the fact that those of us who buy their products have forgiven by now (or don’t care). Nike can take the hit from those who, like me, will never buy another Nike product.

Just a few days ago, Nike signed Vick to an endorsement deal four years after they severed ties with him. Forgive and forget? Nike weighed the pros and the cons and they came to the conclusion that it makes business sense to have Vick out there on their behalf. Nike is banking on the fact that those of us who buy their products have forgiven by now (or don’t care). Nike can take the hit from those who, like me, will never buy another Nike product. I don’t think anyone has forgotten, though. Vick’s name will be forever synonymous with dogfighting. In the end, it seems that forgiving is more important and easier than forgetting. Forgiving is especially easy when it accompanies winning. Winning is very powerful force. Kobe Bryant has been forgiven since his rape charges in 2003. The eight years have helped, but the Lakers’ two championships really helped. Ray Lewis led the Ravens to a win in Super Bowl XXXV and was named its MVP. This was a year after his involvement (to whatever extent) in the stabbing deaths of two people. His past transgressions might even be forgotten at this point. When we talk about Lewis now, we talk about his place in the pantheon of football players, not his past.

I don’t think anyone has forgotten, though. Vick’s name will be forever synonymous with dogfighting. In the end, it seems that forgiving is more important and easier than forgetting. Forgiving is especially easy when it accompanies winning. Winning is very powerful force. Kobe Bryant has been forgiven since his rape charges in 2003. The eight years have helped, but the Lakers’ two championships really helped. Ray Lewis led the Ravens to a win in Super Bowl XXXV and was named its MVP. This was a year after his involvement (to whatever extent) in the stabbing deaths of two people. His past transgressions might even be forgotten at this point. When we talk about Lewis now, we talk about his place in the pantheon of football players, not his past. It has been said that he paid his “debt to society.” I’m not sure what that means. But obviously many people do. If he continues to play as he did in the 2010 season, if by some miracle the Eagles win a Super Bowl, the percentage of people who forgive will increase. That’s how it works, for better or for worse.

It has been said that he paid his “debt to society.” I’m not sure what that means. But obviously many people do. If he continues to play as he did in the 2010 season, if by some miracle the Eagles win a Super Bowl, the percentage of people who forgive will increase. That’s how it works, for better or for worse. 10. Tampa Bay Buccaneers 48 – Oakland Raiders 21 (Super Bowl XXXVII) » At age 37, Rich Gannon threw for 4,689 yards, won the league MVP and took the Raiders to their first Super Bowl since 1983. The oddsmakers favored their top-rated offense by 4 against Jon Gruden’s top-rated defense, but by the time the third quarter ended, it was obvious that defense did, in fact, win championships. Gruden had gotten revenge against his previous team, and the Al Davis affliction in sunny California continued to persist.

10. Tampa Bay Buccaneers 48 – Oakland Raiders 21 (Super Bowl XXXVII) » At age 37, Rich Gannon threw for 4,689 yards, won the league MVP and took the Raiders to their first Super Bowl since 1983. The oddsmakers favored their top-rated offense by 4 against Jon Gruden’s top-rated defense, but by the time the third quarter ended, it was obvious that defense did, in fact, win championships. Gruden had gotten revenge against his previous team, and the Al Davis affliction in sunny California continued to persist. 2007 BCS National Championship Game) » Troy Smith, Ted Ginn and Anthony Gonzalez made the Buckeyes look invincible throughout the season (which included a 24-7 dismantling of defending champions from the University of Texas). Aside from a late game comeback by rival Michigan, Ohio State was never in danger of losing a game. This was supposed to be one of the most lopsided deciding bowl games ever. But Chris Leak, Percy Harvin and some fellow named Tim Tebow had other ideas. After the Buckeyes returned the initial kickoff, Harvin matched—and it was a cakewalk for the remainder. It was lopsided, alright, just on the other side.

2007 BCS National Championship Game) » Troy Smith, Ted Ginn and Anthony Gonzalez made the Buckeyes look invincible throughout the season (which included a 24-7 dismantling of defending champions from the University of Texas). Aside from a late game comeback by rival Michigan, Ohio State was never in danger of losing a game. This was supposed to be one of the most lopsided deciding bowl games ever. But Chris Leak, Percy Harvin and some fellow named Tim Tebow had other ideas. After the Buckeyes returned the initial kickoff, Harvin matched—and it was a cakewalk for the remainder. It was lopsided, alright, just on the other side. 8. Florida Marlins 4 – New York Yankees 2 (2003 World Series) » Money doesn’t always make you happy, and money definitely can’t buy you championships. The Marlins shocked the Yankees (and their $110 million difference in payroll) by riding Josh Beckett to the glory land for the second time in seven years. Along the way, though, they had some extra help from a Cubs fan whose memorabilia-hogging instincts kept the grand prize away for his cursed team.

8. Florida Marlins 4 – New York Yankees 2 (2003 World Series) » Money doesn’t always make you happy, and money definitely can’t buy you championships. The Marlins shocked the Yankees (and their $110 million difference in payroll) by riding Josh Beckett to the glory land for the second time in seven years. Along the way, though, they had some extra help from a Cubs fan whose memorabilia-hogging instincts kept the grand prize away for his cursed team. 7. Greece 1 – Portugal 0 (Euro 2004) » Greece’s improbable run at Euro 2004 was capped with a second defeat of Luiz Felipe Scolari’s Portuguese squad, headlined by Luis Figo and Cristiano Ronaldo, who failed to avenge their opening day loss. Along the way, they also beat France and England. It’s possible to pad this further, but seriously, there shouldn’t be any other data necessary: Greece won Euro 2004 by defeating three powerhouses four times total. That’s the math, and that’s pretty amazing.

7. Greece 1 – Portugal 0 (Euro 2004) » Greece’s improbable run at Euro 2004 was capped with a second defeat of Luiz Felipe Scolari’s Portuguese squad, headlined by Luis Figo and Cristiano Ronaldo, who failed to avenge their opening day loss. Along the way, they also beat France and England. It’s possible to pad this further, but seriously, there shouldn’t be any other data necessary: Greece won Euro 2004 by defeating three powerhouses four times total. That’s the math, and that’s pretty amazing. 6. Maria Sharapova (6-1, 6-4) over Serena Williams (2004 Wimbledon) » Out of nowhere, 13th seeded, 17-year-old Sharapova beats two-time defending champion and #1 seed Williams in straight sets. This was a passing of the torch, of sorts, not unlike Federer beating Sampras in 2001. Of course, Serena continued her dominance for a while longer, but she’ll never forget the spark she provided to Sharapova’s career at Centre Court.

6. Maria Sharapova (6-1, 6-4) over Serena Williams (2004 Wimbledon) » Out of nowhere, 13th seeded, 17-year-old Sharapova beats two-time defending champion and #1 seed Williams in straight sets. This was a passing of the torch, of sorts, not unlike Federer beating Sampras in 2001. Of course, Serena continued her dominance for a while longer, but she’ll never forget the spark she provided to Sharapova’s career at Centre Court. 5. Y.E. Yang (-8) over Tiger Woods (-5) (2009 PGA Championship) » Golf isn’t a head-to-head sport, but when you take into effect that Yang and Woods were paired up for the final round at the Hazeltine National Golf Club, you can imagine how intense it must have been throughout the day. Tiger entered the day with a 2 shot lead before ending the day +3, in the process witnessing the first Asian-born player to win a major on the PGA tour. This was all the more impressive as Yang didn’t start playing golf until age 19. The maturing prodigy was defeated by the budding late-bloomer.

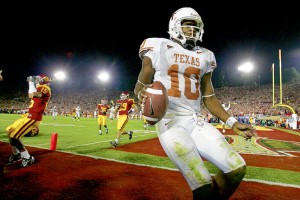

5. Y.E. Yang (-8) over Tiger Woods (-5) (2009 PGA Championship) » Golf isn’t a head-to-head sport, but when you take into effect that Yang and Woods were paired up for the final round at the Hazeltine National Golf Club, you can imagine how intense it must have been throughout the day. Tiger entered the day with a 2 shot lead before ending the day +3, in the process witnessing the first Asian-born player to win a major on the PGA tour. This was all the more impressive as Yang didn’t start playing golf until age 19. The maturing prodigy was defeated by the budding late-bloomer. 4. Texas 41 – USC 38 (2006 Rose Bowl/BCS National Championship Game) » Matt Leinart this. Reggie Bush that. For all the hype the media loves to generate, there’s probably no doubt amongst college football fanatics that this Trojans team was one of the greatest to ever play. But there was one man who, frankly, didn’t give a damn: Vince Young. He had put in the single greatest individual performance I’ve ever witnessed by the time he crossed into the endzone on 4th and 2. While the awe and magic of a game like this may never again be repeated, Young’s lesson in media-founded histrionics will always be remembered.

4. Texas 41 – USC 38 (2006 Rose Bowl/BCS National Championship Game) » Matt Leinart this. Reggie Bush that. For all the hype the media loves to generate, there’s probably no doubt amongst college football fanatics that this Trojans team was one of the greatest to ever play. But there was one man who, frankly, didn’t give a damn: Vince Young. He had put in the single greatest individual performance I’ve ever witnessed by the time he crossed into the endzone on 4th and 2. While the awe and magic of a game like this may never again be repeated, Young’s lesson in media-founded histrionics will always be remembered. 3. Patriots 20 – Rams 17 (Super Bowl XXXVI) » September 11 made New York City a solemn place to live. But for some reason, it felt as if supporting these mediocre “Patriots” would make us all happier. So, we did. Against “the Greatest Show on Turf.” Little did we know that we’d witness the genesis of one of the most hated dynasties in sports history, and that of a man who would end up marrying the world’s highest-paid supermodel and have hair softer than Justin Bieber.

3. Patriots 20 – Rams 17 (Super Bowl XXXVI) » September 11 made New York City a solemn place to live. But for some reason, it felt as if supporting these mediocre “Patriots” would make us all happier. So, we did. Against “the Greatest Show on Turf.” Little did we know that we’d witness the genesis of one of the most hated dynasties in sports history, and that of a man who would end up marrying the world’s highest-paid supermodel and have hair softer than Justin Bieber. 2. Giants 17 – Patriots 14 (Super Bowl XLII) » 18-1.

2. Giants 17 – Patriots 14 (Super Bowl XLII) » 18-1.

Over the 4th of July weekend, Portland Timbers rookie midfielder Darlington Nagbe struck one of the goals of the season against Sporting Kansas City. After Nagbe’s fellow midfielder Jack Jewsbury served up a free kick which was punched away by Kansas City goalkeeper Jimmy Nielsen, the ball traveled directly to Nagbe’s right foot. He juggled the ball once, juggled it again and then struck a devastating shot into the top left corner of the net from outside the box. Thankfully for me, it was Portland’s only goal of the night. My Sporting side won a 2-1 victory on the road, while I got the benefit of watching an enjoyable but harmless goal.

Over the 4th of July weekend, Portland Timbers rookie midfielder Darlington Nagbe struck one of the goals of the season against Sporting Kansas City. After Nagbe’s fellow midfielder Jack Jewsbury served up a free kick which was punched away by Kansas City goalkeeper Jimmy Nielsen, the ball traveled directly to Nagbe’s right foot. He juggled the ball once, juggled it again and then struck a devastating shot into the top left corner of the net from outside the box. Thankfully for me, it was Portland’s only goal of the night. My Sporting side won a 2-1 victory on the road, while I got the benefit of watching an enjoyable but harmless goal. All the same, I can’t dismiss the possibility that the prevalence of Brits is based as much on branding as it is broadcasting. In American culture, the English accent serves as a shorthand in and of itself. The clearest use of this shorthand is Hollywood’s mandatory accent rule of ancient Rome, which stipulates that anyone portraying a Roman must speak in an English accent. This doesn’t mean just hiring English actors. It means that non-English actors must fake an English accent. My personal favorite iteration of this rule occurred in Gladiator, when Russell Crowe (an Australian actor) used an English accent (to speak what historically would have been Latin) in order to portray Maximus Decimus Meridius (a Roman General), a character who the film tells us is actually from Spain.

All the same, I can’t dismiss the possibility that the prevalence of Brits is based as much on branding as it is broadcasting. In American culture, the English accent serves as a shorthand in and of itself. The clearest use of this shorthand is Hollywood’s mandatory accent rule of ancient Rome, which stipulates that anyone portraying a Roman must speak in an English accent. This doesn’t mean just hiring English actors. It means that non-English actors must fake an English accent. My personal favorite iteration of this rule occurred in Gladiator, when Russell Crowe (an Australian actor) used an English accent (to speak what historically would have been Latin) in order to portray Maximus Decimus Meridius (a Roman General), a character who the film tells us is actually from Spain. For soccer in America, the shorthand of an English (or Irish or Scottish) accent is also clear: Guys with accents know a lot about soccer. And in a country where Cheryl Cole may have been fired by American Idol for her Geordie accent, soccer fans make up one of the few groups who are happy to hear an English accent because of the credibility it conveys. Yes, some of those fans are ignorant snobs who just think the accent “sounds better.” But most simply want to hear games called by people who understand the sport.

For soccer in America, the shorthand of an English (or Irish or Scottish) accent is also clear: Guys with accents know a lot about soccer. And in a country where Cheryl Cole may have been fired by American Idol for her Geordie accent, soccer fans make up one of the few groups who are happy to hear an English accent because of the credibility it conveys. Yes, some of those fans are ignorant snobs who just think the accent “sounds better.” But most simply want to hear games called by people who understand the sport. To be honest, I can’t pinpoint a single game or moment that made me a Mets fan. Growing up in Long Island, long summer days were spent playing baseball and home run derby at the park. We’d emulate our favorite players’ batting stances and pitching motions. In particular, I was infamous for my Jeff Innis sidearm delivery impression, and my Daryl Strawberry silky smooth swing was uncanny. My father was particularly enamored with the ‘86 Mets. He loved Keith Hernandez and Gary Carter. We spent many hazy summer nights watching the Mets on TV after he’d get home from work. I loved it when he told me stories of that season, and how the they were unlike any other team he’d ever watched. Shea Stadium in nearby Flushing was a mere 30 minute drive from home, so we’d go to at least one game a season. Combine all the aforementioned factors, and unfortunately, a Mets fan was born.

To be honest, I can’t pinpoint a single game or moment that made me a Mets fan. Growing up in Long Island, long summer days were spent playing baseball and home run derby at the park. We’d emulate our favorite players’ batting stances and pitching motions. In particular, I was infamous for my Jeff Innis sidearm delivery impression, and my Daryl Strawberry silky smooth swing was uncanny. My father was particularly enamored with the ‘86 Mets. He loved Keith Hernandez and Gary Carter. We spent many hazy summer nights watching the Mets on TV after he’d get home from work. I loved it when he told me stories of that season, and how the they were unlike any other team he’d ever watched. Shea Stadium in nearby Flushing was a mere 30 minute drive from home, so we’d go to at least one game a season. Combine all the aforementioned factors, and unfortunately, a Mets fan was born.

There are few better moments in all of sports better than waiting for a crucial pitch to be delivered late in October. If the Mets were to break the curse of being the Mets, this was the perfect moment. There was no one I’d rather have up at the plate than the next batter, Carlos Beltran. 41 homeruns, 116 RBI, All-Star, Gold Glove winner, Silver Slugger winner. This was why the Mets shelled out the big bucks for the quiet centerfielder. First pitch, strike 1. Second pitch, strike 2. I looked at my best friend and fellow Mets fan. No words were needed. As I took a deep gulp and tried to compose myself for what was to follow, an undeniably ominous feeling crept through my bones. Ya gotta believe, they say. Wainwright would pause at the top of the mound for what seemed like an eternity. He then delivered one of the filthiest, nastiest curveballs I’ve ever seen. As the ball dropped 12-6 on the outside corner of the plate and into the catcher’s mitt, Beltran still had his bat on his shoulders. I knew my dreams were shattered. Our clean-up hitter, our big home run man, our hope to break this curse, didn’t even swing the bat. It was all over. I stood stoically as some Yankees fans came over to offer a kind word. It’s hard to recall what they said exactly because the whole bar had become eerily silent, and everything around me had become a blur. Absolutely gutted. Then rage. He didn’t even swing the bat! Just like that, one pitch and order in the universe was restored. The Mets disappointed yet again.

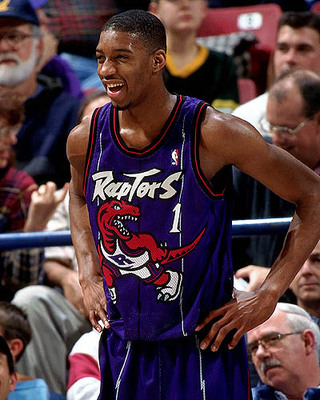

There are few better moments in all of sports better than waiting for a crucial pitch to be delivered late in October. If the Mets were to break the curse of being the Mets, this was the perfect moment. There was no one I’d rather have up at the plate than the next batter, Carlos Beltran. 41 homeruns, 116 RBI, All-Star, Gold Glove winner, Silver Slugger winner. This was why the Mets shelled out the big bucks for the quiet centerfielder. First pitch, strike 1. Second pitch, strike 2. I looked at my best friend and fellow Mets fan. No words were needed. As I took a deep gulp and tried to compose myself for what was to follow, an undeniably ominous feeling crept through my bones. Ya gotta believe, they say. Wainwright would pause at the top of the mound for what seemed like an eternity. He then delivered one of the filthiest, nastiest curveballs I’ve ever seen. As the ball dropped 12-6 on the outside corner of the plate and into the catcher’s mitt, Beltran still had his bat on his shoulders. I knew my dreams were shattered. Our clean-up hitter, our big home run man, our hope to break this curse, didn’t even swing the bat. It was all over. I stood stoically as some Yankees fans came over to offer a kind word. It’s hard to recall what they said exactly because the whole bar had become eerily silent, and everything around me had become a blur. Absolutely gutted. Then rage. He didn’t even swing the bat! Just like that, one pitch and order in the universe was restored. The Mets disappointed yet again. Tracy Lamar McGrady, Jr. was drafted 9th overall by the Toronto Raptors in the 1997 NBA Draft. He came straight out of high school and mainly played a reserve role in his first two seasons. A year after T-Mac’s arrival, the Raptors drafted his cousin Vince Carter with the 5th pick: The high flying duo instantly built expectations for the Canadian franchise. They finally led the Raptors to a playoff berth in 2000 only to get swept by the Knicks in the first round. Then, in order to escape the shadow of his older cousin, he forced the hand of the Raptors into a sign-and-trade that sent him to the Orlando Magic.

Tracy Lamar McGrady, Jr. was drafted 9th overall by the Toronto Raptors in the 1997 NBA Draft. He came straight out of high school and mainly played a reserve role in his first two seasons. A year after T-Mac’s arrival, the Raptors drafted his cousin Vince Carter with the 5th pick: The high flying duo instantly built expectations for the Canadian franchise. They finally led the Raptors to a playoff berth in 2000 only to get swept by the Knicks in the first round. Then, in order to escape the shadow of his older cousin, he forced the hand of the Raptors into a sign-and-trade that sent him to the Orlando Magic. But T-Mac had Yao: That should mean something, right? But those Rockets fans who’ve obsessed over our pitfalls know better. There’s no need to discuss Yao’s fragility as that’s deserving of its own article. Yao was (and still is) the Rockets’ cash cow, whether the organization admits it or not. Retaining Yao, even into next year regardless of how much of a liability his injuries have become, is important if only because Yao is a significant financial asset. But Yao’s body and game were never meant to be paired with someone like T-Mac. In his prime, T-Mac represented an ideal NBA body: 6’9″ with a 7’3″ wingspan, 42-inch vertical jump, 235 pounds with only 8% body fat and ran the 40-yard dash in less than 4.5 seconds. He represented the perfect combination of height, weight, speed and strength to be successful in the league—a build like LeBron but with T-Mac’s quickness making up for his lack of similar upper body strength. This quickness suited him a fast-paced system, not one that has to have a half-court set with Yao. In addition, Yao’s game has always been easily neutralized: Too uncoordinated to catch quick passes, too tall to have true success with his back facing the basket, too slow and un-athletic to defend against players that would front him. The list goes on. I’m a fan of Yao only because the man always says and does the right thing and has a lot of heart. But heart only gets you so far. I’ve never met anyone who agreed that the two superstars’ games complemented each other, but everyone agreed that they were indeed “superstars” and would bring in the “kwan” and “show the Rockets the money.” (Jerry Maguire quotes seem quite fitting when discussing money and heart together.) The Rockets would’ve had more success if they had traded Yao for versatile and mobile big men, or if they had traded T-Mac for knock down shooters and defenders (something that Mark Cuban would have done without hesitation)—but the Rockets held onto their “superstars” as money in the pocket instead of building a better ball club to advance to the second round and beyond. The failures of Team USA basketball in the early 2000s have taught us that you can’t just stick a bunch of good players together and expect to win. They have to gel and complement each other. Let’s put this into a statistical perspective: Until the end of the 2007 season, the Rockets won 59% of games with Yao on the floor and 70% without.

But T-Mac had Yao: That should mean something, right? But those Rockets fans who’ve obsessed over our pitfalls know better. There’s no need to discuss Yao’s fragility as that’s deserving of its own article. Yao was (and still is) the Rockets’ cash cow, whether the organization admits it or not. Retaining Yao, even into next year regardless of how much of a liability his injuries have become, is important if only because Yao is a significant financial asset. But Yao’s body and game were never meant to be paired with someone like T-Mac. In his prime, T-Mac represented an ideal NBA body: 6’9″ with a 7’3″ wingspan, 42-inch vertical jump, 235 pounds with only 8% body fat and ran the 40-yard dash in less than 4.5 seconds. He represented the perfect combination of height, weight, speed and strength to be successful in the league—a build like LeBron but with T-Mac’s quickness making up for his lack of similar upper body strength. This quickness suited him a fast-paced system, not one that has to have a half-court set with Yao. In addition, Yao’s game has always been easily neutralized: Too uncoordinated to catch quick passes, too tall to have true success with his back facing the basket, too slow and un-athletic to defend against players that would front him. The list goes on. I’m a fan of Yao only because the man always says and does the right thing and has a lot of heart. But heart only gets you so far. I’ve never met anyone who agreed that the two superstars’ games complemented each other, but everyone agreed that they were indeed “superstars” and would bring in the “kwan” and “show the Rockets the money.” (Jerry Maguire quotes seem quite fitting when discussing money and heart together.) The Rockets would’ve had more success if they had traded Yao for versatile and mobile big men, or if they had traded T-Mac for knock down shooters and defenders (something that Mark Cuban would have done without hesitation)—but the Rockets held onto their “superstars” as money in the pocket instead of building a better ball club to advance to the second round and beyond. The failures of Team USA basketball in the early 2000s have taught us that you can’t just stick a bunch of good players together and expect to win. They have to gel and complement each other. Let’s put this into a statistical perspective: Until the end of the 2007 season, the Rockets won 59% of games with Yao on the floor and 70% without. Never did I dream that we would acquire both of you. Never did I dream that it would quickly turn into a nightmare. It was elating in the moment, though, watching you guys flip a puck to see who would wear #23.

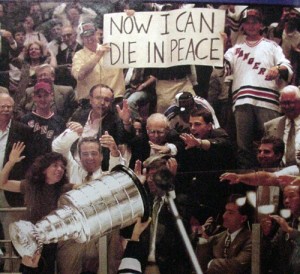

Never did I dream that we would acquire both of you. Never did I dream that it would quickly turn into a nightmare. It was elating in the moment, though, watching you guys flip a puck to see who would wear #23. Still, after Jagr left you were named captain. Rightly so. You were fulfilling the dream of millions in the NY Metro area—the entire sports fan world, really—to play for the team you grew up rooting for. In explaining your departure from Buffalo you explained to the fans that it was like a kid from Rochester being offered a chance to play for the Sabres. You had to take it. Just that fact made you instantly beloved by fans of a certain generation (mine, born in the early 80s and older), though your diminishing skills and silent, lead-by-example style did nothing to impress younger fans who were not sated by the Stanley Cup win in 1994 as my generation was. They could not identify with the famous “Now I Can Die in Peace” banner held up that night. They didn’t witness a cup.

Still, after Jagr left you were named captain. Rightly so. You were fulfilling the dream of millions in the NY Metro area—the entire sports fan world, really—to play for the team you grew up rooting for. In explaining your departure from Buffalo you explained to the fans that it was like a kid from Rochester being offered a chance to play for the Sabres. You had to take it. Just that fact made you instantly beloved by fans of a certain generation (mine, born in the early 80s and older), though your diminishing skills and silent, lead-by-example style did nothing to impress younger fans who were not sated by the Stanley Cup win in 1994 as my generation was. They could not identify with the famous “Now I Can Die in Peace” banner held up that night. They didn’t witness a cup. You and Ryan Callahan did Ranger fans proud at the Vancouver Olympics, but we wondered why you lacked that same drive when you played for us. We saw the same Cally on the ice at the Garden as we saw in Vancouver,, but you were different, like that jersey mattered more to you than the Ranger jersey. I’m sure it didn’t, but it felt that way at times.

You and Ryan Callahan did Ranger fans proud at the Vancouver Olympics, but we wondered why you lacked that same drive when you played for us. We saw the same Cally on the ice at the Garden as we saw in Vancouver,, but you were different, like that jersey mattered more to you than the Ranger jersey. I’m sure it didn’t, but it felt that way at times.

9. Portland Trail Blazers: 1970/71 – 1989/90 (NBA)

9. Portland Trail Blazers: 1970/71 – 1989/90 (NBA) 8. Minnesota North Stars: 1967/68 – 1973/74 (NHL)

8. Minnesota North Stars: 1967/68 – 1973/74 (NHL) 7. Toronto Blue Jays: 1977 – 1996 (MLB)

7. Toronto Blue Jays: 1977 – 1996 (MLB)  6. Pittsburgh Steelers: 1963 – present (NFL)

6. Pittsburgh Steelers: 1963 – present (NFL) 5. California Golden Seals: 1970/71 – 1973/74 (NHL)

5. California Golden Seals: 1970/71 – 1973/74 (NHL) 4. Milwaukee Brewers: 1978 – 1993 (MLB)

4. Milwaukee Brewers: 1978 – 1993 (MLB) 3. Montreal Expos: 1969 – 1991 (MLB)

3. Montreal Expos: 1969 – 1991 (MLB) 2. Hartford Whalers: 1979/80 – 1991/92 (NHL)

2. Hartford Whalers: 1979/80 – 1991/92 (NHL) 1. Vancouver Canucks: 1970/71 – 1979/1980 (NHL)

1. Vancouver Canucks: 1970/71 – 1979/1980 (NHL) “I want the Klitschko’s heads, plain and simple no doubt. You and your brother, and I’m going to have them. This year, I’m going to have ‘em . That’s what I’m in this game for.”

“I want the Klitschko’s heads, plain and simple no doubt. You and your brother, and I’m going to have them. This year, I’m going to have ‘em . That’s what I’m in this game for.” Haye’s style can best be described as 80% of Roy Jones’ skill combined with 105% of Jones’ power. Haye is not a natural heavyweight, standing only 6’2 and weighing only 220 pounds. A questionable chin—in other words, his ability to withstand physical trauma to the head without being knocked unconscious—hasn’t stopped Haye from producing action fights as a heavyweight; he was able to knock out John Ruiz and seriously hurt Nikolay Valuev. There’s no higher compliment you can give a fighter than, “He has a questionable chin, but he’s willing to mix it up.” Regardless of whether he wins or loses, no one can say a David Haye fight is boring.

Haye’s style can best be described as 80% of Roy Jones’ skill combined with 105% of Jones’ power. Haye is not a natural heavyweight, standing only 6’2 and weighing only 220 pounds. A questionable chin—in other words, his ability to withstand physical trauma to the head without being knocked unconscious—hasn’t stopped Haye from producing action fights as a heavyweight; he was able to knock out John Ruiz and seriously hurt Nikolay Valuev. There’s no higher compliment you can give a fighter than, “He has a questionable chin, but he’s willing to mix it up.” Regardless of whether he wins or loses, no one can say a David Haye fight is boring.